Replacement theology – also called Supersessionism and fulfillment theology – is a paradigm of the Scriptures (especially the NT) which interprets the New Testament church as being a replacement, fulfillment, or completion of the promises made to ethnic Israel in the Old Testament. Historically, this view grew in tandem with the decrease of Jewish leadership in the church within the first two centuries after the ascension. The reason for the article is because I hear a lot of people, even leaders, wanting to distance themselves from replacement theology these days. While this is an excellent thing, it also seems that there is little understanding on what replacement theology is. This tends to lead to a dynamic which regards the church as replacing Israel while giving lip service to the denial of such doctrines.

Replacement theology – also called Supersessionism and fulfillment theology – is a paradigm of the Scriptures (especially the NT) which interprets the New Testament church as being a replacement, fulfillment, or completion of the promises made to ethnic Israel in the Old Testament. Historically, this view grew in tandem with the decrease of Jewish leadership in the church within the first two centuries after the ascension. The reason for the article is because I hear a lot of people, even leaders, wanting to distance themselves from replacement theology these days. While this is an excellent thing, it also seems that there is little understanding on what replacement theology is. This tends to lead to a dynamic which regards the church as replacing Israel while giving lip service to the denial of such doctrines.

The issue of “replacement” deals with more than the people who inherit the promises, rather it has to do with the nature of the promises themselves.

25 For I do not want you, brethren, to be uninformed of this mystery–so that you will not be wise in your own estimation–that a partial hardening has happened to Israel until the fullness of the Gentiles has come in; (Rom 11:25 NASB)

Paul explained to the Roman church – at the time a complicated mixture of Jew and Gentile – that arrogance results from the misunderstanding of the circumstances surrounding the nation of Israel right now. It is clear to anyone familiar with the Old Testament that Israel is not presently experiencing anything even remotely close to what they were promised in the Old Testament. This places us in a dilema. Either we must still be waiting for the fulfillment of the promises, OR we must redefine the promises in some way in order to maintain some sense of having “arrived” within the Christian community.

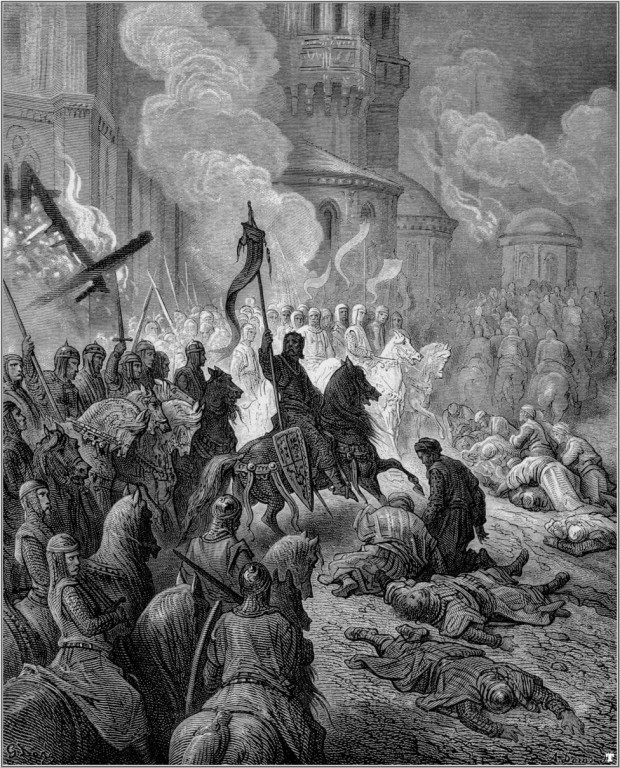

As mentioned before, this decision was made in the second and third centuries while the Jewish leadership in the church was being replaced with Greek leadership. One significant milestone in the historic development of replacement theology’s current dominance of the theological landscape of Christianity happened in the mid 3rd century with a school that formed in Alexandria, Egypt. Under the leadership of Origen, the Bible school taught a synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christianity fueled primarily by the introduction of an allegorical interpretation of the Scripture. Prior to the formation of this school, there were no alternative methods of interpreting the Old Testament Scriptures within the Christian community – only the literal interpretation. (While Philo [20 B.C. – 50 A.D.] – a Jewish philosopher who also lived in Alexandria – also taught this allegorical approach to the Old Testament, there are not records prior to Origen that his writings were significantly impactful within the Christian community.)

This hermeneutic (or Bible interpretation method) was the forerunner for replacement theology – or as Paul called it, Christian Gentiles ‘being wise in their own estimation’. (cf. Rom. 11:25) Zion, Israel, and Jerusalem became terms which were referring to the redeemed people of God rather than to actual geography in the middle east. Moab, Egypt, Assyria, Persia, Babylon became spiritualized enemies of the spiritual Israel.

The next logical conclusion within the allegorical interpretive method was that the ‘children’ of Israel were simply the spiritual children who were born again into the new covenant. (Of course, this ignores the fact the New Covenant was promised to the Jewish people) So, in reality, replacement theology isn’t a haphazard insertion of your name in place of Israel when interpreting blessings promised to them. It is simply an outworking of a greater overarching problem: the spiritualization of plain Scripture so that it revolves around my existence rather than the Jewish Messiah or even around God.

Hopefully, this frames the argument a bit differently. It isn’t simply the reinterpretation of the people, but of the promises themselves. The only way that replacement theology (or any of the various schools of interpretation of it’s kind) can work in the real world is that the promises have to be reinterpreted as well. So, not only does Zion mean the church, but now the promises of leadership, wealth, influence, and blessing have to be allegorized as well.

Ezekiel 37 is a very common example. The Lord shows Ezekiel the moment in the future when the righteous will be resurrected from the grave. This was a common expectation, clearly explained through the law and the prophetic books. (cf. Dan. 12:2-3, Is. 26:19, Heb. 6:4, Rom. 8:23) The resurrection of the dead is a CLEARLY prophesied event in the Old and New Testaments when the Messiah returns to the earth and resurrects the bodies of the saints. This is the time when death is abolished and creation restored.

Ezekiel 37 is CLEARLY a reference to this event, and Ezekiel clearly understands it this way. Allegorical interpreters use this passage as an arbitrary promise that God will raise up people who are spiritually dead to be spiritually alive again. Thus, another promise given to Israel is reinterpreted as not only being ABOUT us, but about something else altogether. This is the real problem with allegorical interpretation of Scripture. It provides license to alter the Biblical hope to another hope of our own design. This way we become wise in our own estimation. (cf. Rom. 11:25)

The insistence of interpreting ‘Israel’ as Israel can seem trivial until you realize that all of the promises have to be reinterpreted at the same time. I realize this is a tough pill for some to swallow, but I’d prefer truth that is costly to believe than a lie that is cheap. In the end only what is real will matter. I will leave you with one of my favorite quotes. Thomas C. Oden wrote in Vol. 2 of his systematic theology:

The decisive question of Christian testimony is not whether it is palatable, but whether it is true.